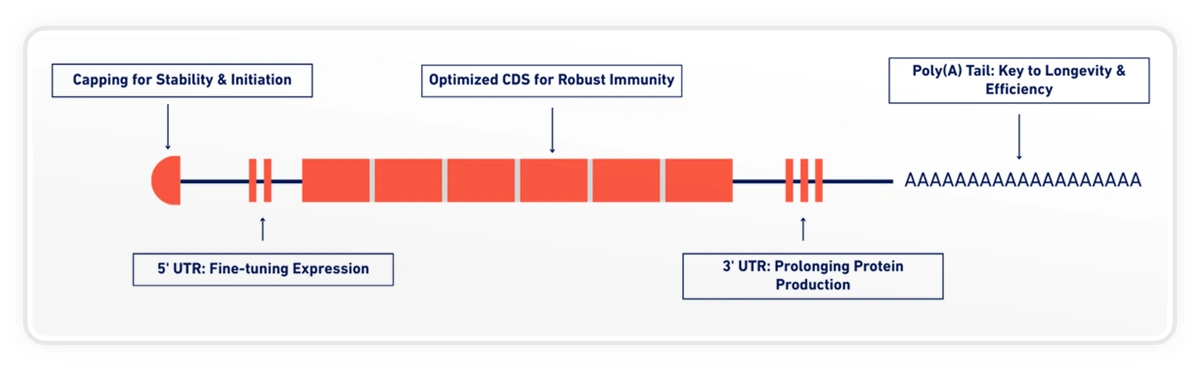

The last few years have firmly established mRNA as a viable and powerful therapeutic platform. From infectious disease vaccines to emerging oncology applications, mRNA has demonstrated both biological effectiveness and unprecedented development speed.

As the field matures, attention is shifting from whether mRNA works to how efficiently it can be designed, tested, and optimized. Increasingly, that question hinges on parts of the workflow that sit far upstream of delivery systems and formulations and are embedded in the DNA templates that quietly shape everything downstream.

One such element is the poly(A) tail.

A small sequence with outsized influence

Poly(A) tails play a central role in mRNA stability, translation efficiency, and protein yield. Numerous studies have shown that tail length influences how long an mRNA persists in the cell and how efficiently it is translated, particularly for larger and more complex constructs such as self-amplifying RNA [1][2].

Because of this, poly(A) length is frequently discussed as a design consideration but rarely explored as a variable that can be systematically tuned.

Where practical constraints begin to shape scientific decisions

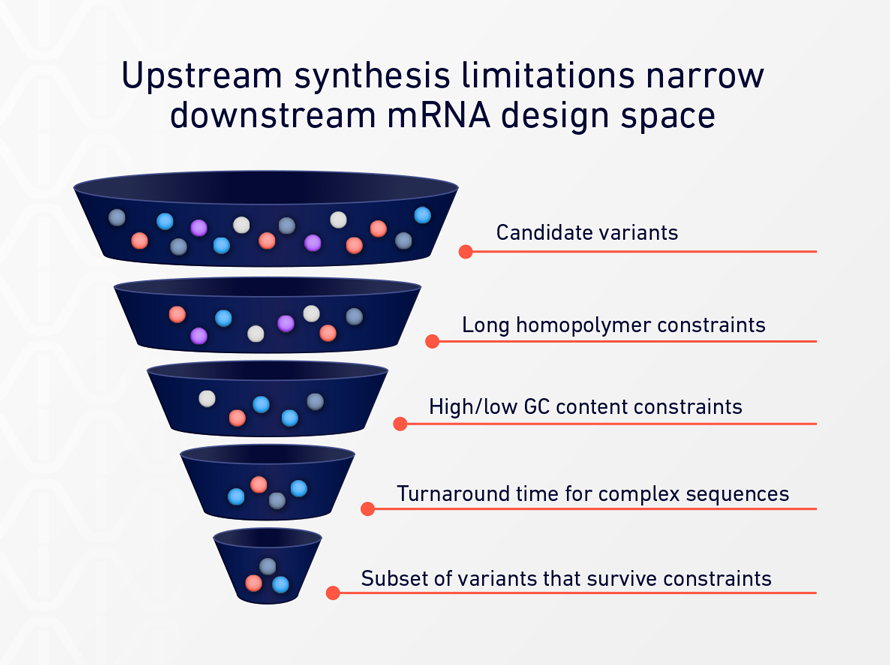

Although poly(A) sequences are conceptually simple, they are technically difficult to produce with precision using conventional DNA synthesis methods. Long homopolymer stretches push against the limits of chemical synthesis, leading to lower yields, higher error rates, and longer turnaround times.[3]

As a result, researchers often encounter implicit constraints: poly(A) lengths that are “good enough,” design choices shaped by vendor capabilities, and iteration cycles slowed by external dependencies.

These limitations rarely stop a project outright. Instead, they influence how many variants get tested, how broadly design space is explored, and how quickly teams can respond to experimental results.

Iteration speed as a determinant of progress

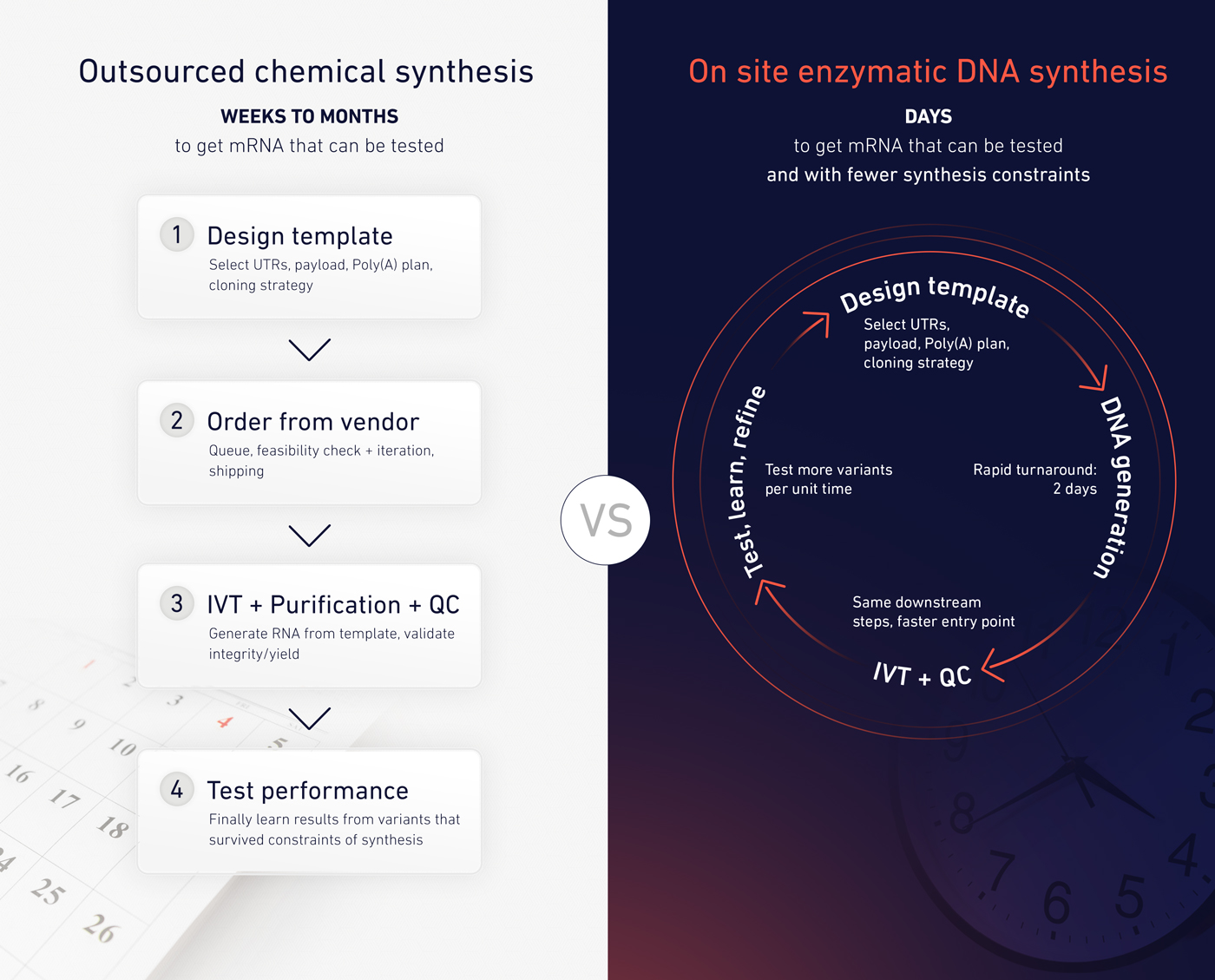

In many mRNA programs, the scientific challenge is no longer identifying promising design directions but testing them efficiently. As constructs grow longer and more complex, particularly in saRNA and personalized vaccine applications, the time required to generate and modify DNA templates becomes increasingly consequential.

When certain sequence features are slow or difficult to change, they are often fixed early in a project and revisited only after downstream results raise questions, if they are revisited at all. Over time, these practical constraints shape experimental strategy just as much as biological insight does.

Poly(A) tails are a clear example of how this dynamic plays out: widely acknowledged as important yet often explored narrowly due to practical constraints rather than scientific preference.

Regaining flexibility at the sequence level

Recent advances in enzymatic DNA synthesis and benchtop DNA printing are beginning to change how researchers interact with DNA4. By making difficult or repetitive sequences easier to generate on demand, these tools shift DNA from a bottleneck to a controllable input.

In this context, poly(A) tails become one of many sequence features that can be adjusted, tested, and refined as part of a continuous design cycle rather than a one-time specification.

What changes when poly(A) becomes adjustable

For teams iterating on mRNA or saRNA designs, poly(A) is a recurring “known-to-matter” parameter that often gets locked early because it’s slow or costly to change. SYNTAX platform makes it practical to treat poly(A) length as an experimental variable and enabling on-demand synthesis of long A/T-rich sequences and rapid template generation in-house.

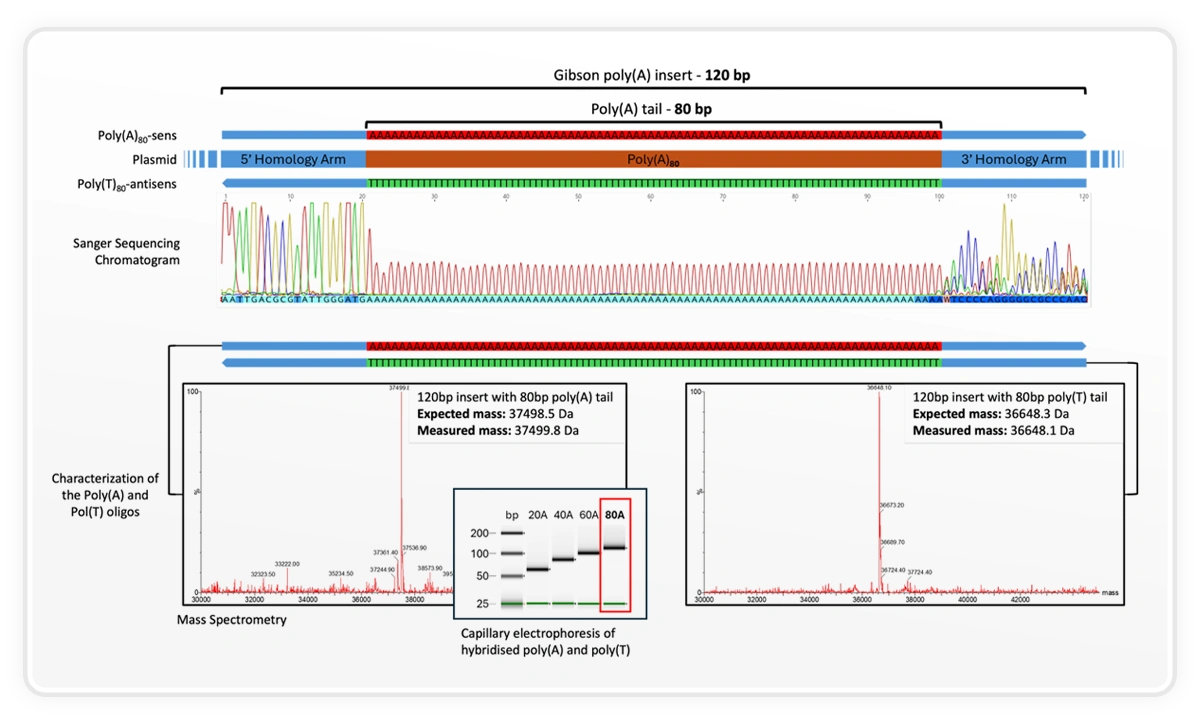

Using the SYNTAX benchtop DNA printer, DNA Script synthesized a 120 bp insert containing an 80 bp poly(A) tail and validated it using mass spectrometry, Sanger sequencing, and capillary electrophoresis. The measured mass closely matched expectation (37,498.5 Da expected; 37,499.8 Da measured), illustrating the level of control and fidelity achievable for long homopolymer regions that are traditionally difficult to synthesize.

See the SYNTAX in action and explore what’s possible with on-demand oligo synthesis by watching our recent webinar

DISCOVER SYNTAXLooking upstream to move faster downstream

As mRNA platforms continue to evolve, the sources of friction in development workflows are becoming more visible. Many of them reside upstream, embedded in assumptions about how DNA is produced and how quickly designs can change.

Poly(A) tails offer a useful lens into this shift, revealing how upstream control increasingly determines the pace of downstream innovation.

As researchers push toward more complex, responsive, and personalized RNA therapies, the ability to iterate rapidly at the sequence level will increasingly shape what is possible and how quickly it can be achieved.

![[Webinar Recap] New Approaches to Gene Construction Using Our Enzymatic DNA Synthesis](https://www.dnascript.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Design-sans-titre-300x300.jpg)